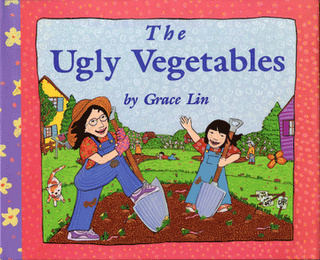

My first published book was, The Ugly Vegetables, a story about my mother and I and the Chinese vegetables we grew when I was a child. One look at the cover and you can see it’s chock full of the multicultural label.

My first published book was, The Ugly Vegetables, a story about my mother and I and the Chinese vegetables we grew when I was a child. One look at the cover and you can see it’s chock full of the multicultural label.And that label, as anyone who has experienced it knows, is quite a double-ended sword. However, when it was published I was still a bit green about the genre. So it was with a little surprise when a fellow striving author/illustrator (not a blue rose girl, btw) said to me, “It’s a good that you’re using your culture, that’s what’s getting you published.”

Was it? Suddenly, the validation that I had broken through the publishing wall was marred by the idea that I had somehow squeezed through a back window. Was I only getting published because of my heritage and subject matter? Was I cheating? Was I selling out my culture for a career?

And this fear was something that haunted me. During that first year of publication, I constantly felt ill at ease, as if I was a chicken floating with swimming swans. I hadn’t intended on getting on a platform for diversity in children’s literature—I had just wanted to get a story I loved published. But, without meaning to, my book was seen (by those who read it, the numbers of that is another story) as representative of the underserved Asian-American experience. And who was I to represent that? I felt, in my desperation to get published, I had faked my way in.

So soon after (during the discussions for another project) when an editor asked me to consider changing my Asian girl character to a Caucasian boy, I should’ve felt a sense of satisfaction and relief. The reasons were good— changing the character would make it so that the book wouldn’t be considered multicultural, its sales wouldn’t be limited and I, as an author, wouldn’t be pigeon-holed. But, instead, I was uneasy.

Suddenly, I found myself not caring if I was getting published for the wrong reasons or I wasn’t selling enough books for the right ones. Somehow, given the opportunity to prove I was publishable without my heritage seemed a pale consolation prize when compared to creating a book that was true to my vision, the readers who loved my books and the child I was many years ago.

And it’s not that I’ll never do a book with a Caucasian boy (I would do a book on anything if I felt it was right) or that my books are meant to preach (horrors!). But, I realized that being able to publish my work was a gift not to be squandered on something soulless. And my soul is Asian-American.

So, strangely, it was the unsettling nature of this editor’s request that made me find my balance. It sifted away my fears, the practical reasoning and the backhanded compliments and left me proud of what I am, a multicultural author.